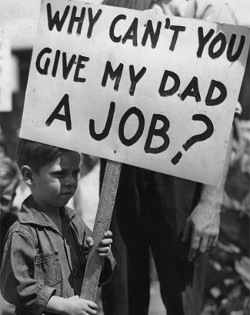

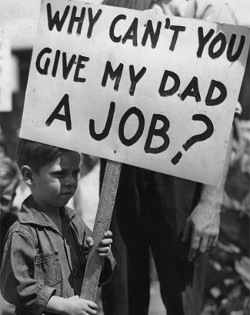

FAMILY LIFE

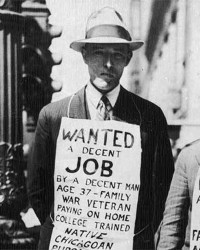

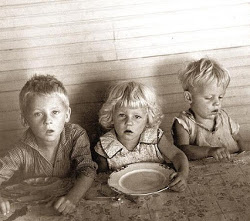

Families were hit especially hard by the Great Depression. It was often necessary for one parent to leave the family home and travel in search of work. Unemployed and

penniless relatives sometimes were taken in to already crowded households, adding to the misery and difficulty of keeping everyone clothed and fed. Children, especially the

very young, were unable to understand what was happening to them and why their lives had changed so drastically. In some case, entire families were turned out of their homes to

wander the country in search of food and shelter. Throughout the decade, marriage and birth rates declined and divorce rates rose. Men, who were used to thinking of themselves

as breadwinners, were filled with feelings of failure. Many took to drink to try to soften the pain.

That is not to say that all American families became dysfunctional during this time. Some faced hard times with determination and courage, and drew upon the strength of family

bonds to hold things together. In this way they were able to maintain a somewhat harmonious home atmosphere, even with the wolf at their door.

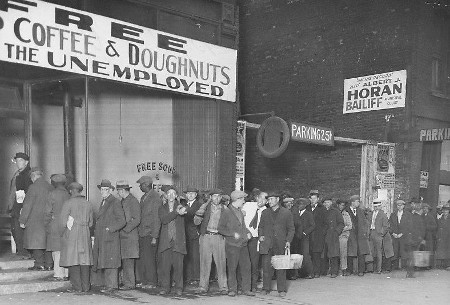

Traditional gender roles were challenged as well. It became necessary for many married women to take whatever work was available to help keep their households together. With wages

continually falling and fewer jobs available each year, men and women alike were often forced to accept jobs that they would have never dreamed they would take. In some cities, particularly in

New York, adults and children alike were reduced to selling apples on the sidewalks.

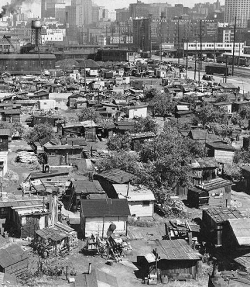

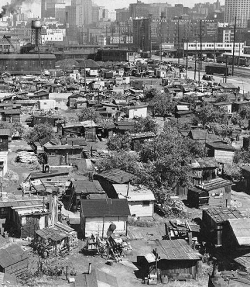

HOOVERVILLE

As the number of those without shelter rose significantly during the first years of the decade, makeshift dwellings of scrap lumber and other salvaged material appeared on whatever

vacant land could be found in and around the cities. Dubbed "Hoovervilles" because of the widespread belief that President Hoover wasn't concerned with providing relief to the people, these

shanty towns became an iconic symbol of the era.

Although some have drawn a parallel between these communities and the homeless encampments of the present day, there were

some marked differences. Hooverville residents tried to locate their homes near rivers or sources of water. Many grew small gardens near their shacks to provide at least a small amount

of food. Some were able to furnish their humble abodes with tables and chairs from their former homes. One privately funded community in St Louis had an unofficial elected mayor and

its citizens organized churches and other community associations. Most Hooverville residents were more than willing to work and would take whatever employment was available.

Although attempts were made to make the best of a bad situation, these communities were unsanitary and unhealthy. Some local governments fought against the shanty towns by evicting

residents and clearing away the dwellings. Others, mindful of the fact that these people were there out of necessity rather than choice, reacted with an unofficial policy of tolerance.

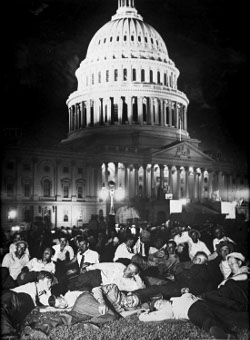

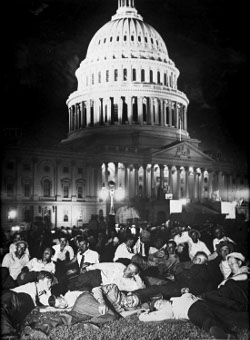

One famous Hooverville was erected in Washington DC in the summer of 1932 by members of the so-called "Bonus Army", a mass of more than thirty thousand World War I veterans who marched

to the nation's capital from across the nation to demand early payment of bonus certificates authorized by Congress in 1924 and made payable in 1945. The veterans held daily marches

in support of their cause and lobbied Congress for action. A bill introduced in the House of Representatives to provide early payment of the bonuses passed, but was defeated in

the Senate.

After attempts to convince the protesters to leave were unsuccessful, US Attorney General William D Mitchell ordered the veterans to disperse. When that order was ignored,

President Hoover sent two Army units, led by General Douglas MacArthur and Major George S Patton, to clear the area. The resulting action left 55 veterans wounded. After the community

was cleared, the Army set fire to the structures.

In contrast, a second demonstration the following year was treated much differently. Newly minted President Roosevelt, provided the

marchers with a campsite in Virginia and three meals a day. Although attempts were made to negotiated with the protesters, this new Bonus Army went away empty handed as well.

The majority of these makeshift communities lasted throughout the decade, although there was some marginal relief in most areas in the later years. Most were emptied and destroyed

by the early 1940s.

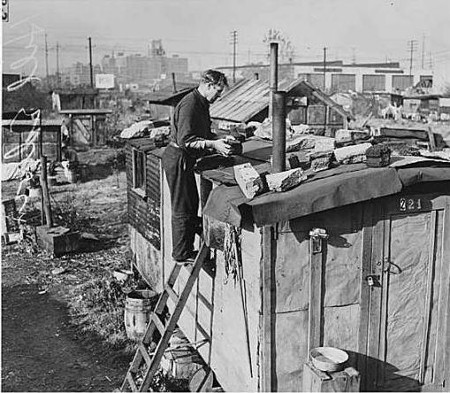

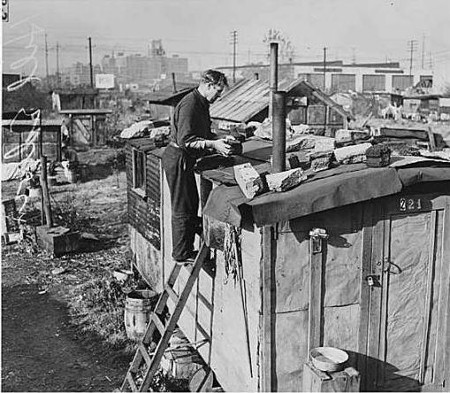

A Hooverville resident working on his makeshift cabin.